“Sleep Walking Now and Then,” by Richard Bowes, is a weird, futuristic novelette about an interactive theater production in The Big Arena (aka New York City) and the mystery surrounding its inspiration.

This novelette was acquired and edited for Tor.com by consulting editor Ellen Datlow.

Rosalin Quay, the set and costume designer, stood in a bankrupt Brooklyn warehouse staring at the rewards of a long quest. Inside a dusty storage space were manikins. Stiff limbed, sexless ones from the early 20th century stood alongside figures with abstract sexuality (which is how some described Rosalin) from the early 21st.

But the prime treasure of this discovery was dummies from a critical moment of change. Manikins circa 1970 were fluid in their poses, slightly androgynous but still recognizably male or female. The look would be iconic in the immersive stage design which she had been hired to assemble.

The warehouse manager, Sonya, was tall, strong, and desperate. Rosalin, who had an eye for these things, placed her on the wrong side of thirty but with a bit of grace in her movements. Sonya brought up computer records on the palm of her hand. The owner of the manikins had stopped paying rent during the crash of 2053. The warehouse would shut down in two days and was unloading abandoned stock at going-out-of-business prices.

A pretty good guess on Rosalin’s part was that Sonya came to New York intending to be a dancer/actor, had no luck, and was about to be unemployed: a common tale in the city everyone called the Big Arena.

“These pieces are for my current project,” Rosalin said, and sent her an address. “I consider finding you and the manikins at the same moment an interesting coincidence. It would be to your advantage to deliver them personally.”

She believed she saw a bit of what was called espontáneo in the younger woman.

ONE

Jacoby Cass awoke a few days later in the penthouse of a notorious hotel. The Angouleme, built in 1890, had stood in the old Manhattan neighborhood of Kips Bay for a hundred and seventy years. Its back was to the East River and sunlight bounced off the water and through the uncurtained windows.

Cass rose and watched tides from the Atlantic swirl upstream. Water spilled over the seawall and got pumped into drainage ditches. In 2060, every coastline on earth that could afford floodwalls had them. The rest either pumped or treaded water.

Like many New Yorkers, Jacoby Cass saw the rising waters as a warning of impending doom but, like most of them, Cass had bigger worries. None are as superstitious as the actor, the director, or the playwright in the rehearsals of a new show. And for his drama Sleep Walking Now and Then, which was to be put on in this very building, Jacoby Cass was all three.

Weeks before, his most recent marriage had dissolved. She kept the co-op while he slept on a futon in the defunct hotel. Most of his clothes were still in the suitcases in which he’d brought them.

All was barren in the room except for a rack holding a velvet-collared frock coat, an evening jacket, silk vests, starched white shirts and collars, opera pumps, striped trousers, arm and sock garters, a high silk hat, and pairs of dress shoes sturdy as ships. He was going to play Edwin Lowery Nance, the man who had built this hotel. And this was his wardrobe for Sleep Walking.

Cass’s palm implant vibrated. Messages flashed: Security told him a city elevator inspector was in the building. His ex-wife announced she was closing their safe-deposit box. A painting crew for the lower floors was delayed. His eyes skimmed this unpleasant list as he tapped out a demand for coffee.

An image of the lobby of The Angouleme popped up. The lobby looked as it had when he’d run through a scene there the week before. Relentless sunlight showed the cracks in the dark wood paneling, the peeling paint and sagging chandeliers. The place was bare of furniture and rugs.

Then an elevator door opened and Cass saw himself step out with two other actors. The man and the woman wore their own contemporary street clothes and carried scripts. Cass, though, wore bits of his 1890s costume—a high hat, a loosely tied cravat. He was Edwin Lowery Nance showing wealthy friends the palace he’d just built, where he would die so mysteriously.

“My good sir and lovely madam,” he heard himself say, “I intend this place to be a magnet, attracting a clientele which aspires to your elegance.” They played out the scene as he’d written it, in that shoddy space devoid of any magic. The other two actors were still learning their lines. But Cass found his own rendition of the lines he’d written flat and ridiculous.

Irritated, wondering why this had been sent to him, Cass was about to close his fist and erase the messages when he heard Rosalin’s voice, with its traces of an indefinable (and some said phony) European accent.

“Not an impressive outing. But I believe if you try again this evening, you will find everything transformed.”

Rosalin and Jacoby Cass had worked together over the years without ever becoming more than acquaintances. But Cass found a ray of hope in the message and decided to grasp it.

His coffee was delivered by the new production assistant, a tall and tense young lady. Cass noted her legs in pants down to the shoe tops, though autumn fashion had decreed bare legs for women and long pants for men. Quite a reverse of the styles of the last few years.

He could imagine her life in the Big Arena with multiple aspiring artists/roommates all scraping by in a deteriorating high-rise. This was Rosalin’s protégé. He thought her name was Sonya but wasn’t positive. At the outset of his career, almost forty years before, he had learned to be nice to the assistants, because one never knew which of them would end as a huge name. So he smiled the smile that had made him a star and took the coffee into the bathroom.

Water pressure wasn’t good, and the pipes were rusty, but like the building itself, the pipes and wiring pretty much worked. Twenty minutes later, shaved, showered, purged, and scented, he donned modern underwear then got dressed from the costume rack: a starched shirt minus the collar, trousers held up with suspenders, an unbuttoned vest, and slippers.

A palm message told him the elevator inspector was waiting. He opened his bedroom door and walked intothe big skylighted room that had once been the office/den of Edwin Lowery Nance, whose unproven murder haunted the Angouleme Hotel.

In Nance’s lair all was old wood and brass and it had not aged well. For scores of years The Angouleme had followed a downward path before being seized by the city. Bright sun streamed down and highlighted the scarred desk and worn rugs. After dark and in the low glow of early electricity, all would have to appear mysterious, rich, and rotten. Everything depended on that.

Down a very short corridor lay the bedchamber of Evangeline, daughter of Edwin Lowery Nance, and more famous in her time than Lizzie Borden. Through the open door Cass could see the curtains on the canopied bed parted to display a beautifully dressed Parisian doll. Legend demanded it. Just as Lizzie will always be the harridan with the axe, Evangeline Nance was the sleep walking child with a doll under her arm.

Jacoby Cass’s career had high points which many in this city remembered. His Hamlet was set in an abandoned seminary where audience members could pick flowers with Ophelia, help dig graves or secretly poison swords.

The Downton Abbey he staged in the Frick Museum was a week-long twenty-four-hour-a-day drama built around an antique television show. Customers took tea with aristocrats, spied on lovers, searched closets and dresser drawers for clues and scandal. It ran for years and rescued the bankrupt museum for a time.

Once, Cass was spoken of as a theatrical giant: Barrymore and Ziegfeld combined. But at the moment he was coming off flops on stage, screen, and net. He’d recently been approached to take the film role of a hammy older actor. He’d turned it down. But the backers of Sleep Walking Now and Then were not a patient crew, and in his bad moments he wondered if he’d regret not taking the part. This show would click fast or die fast.

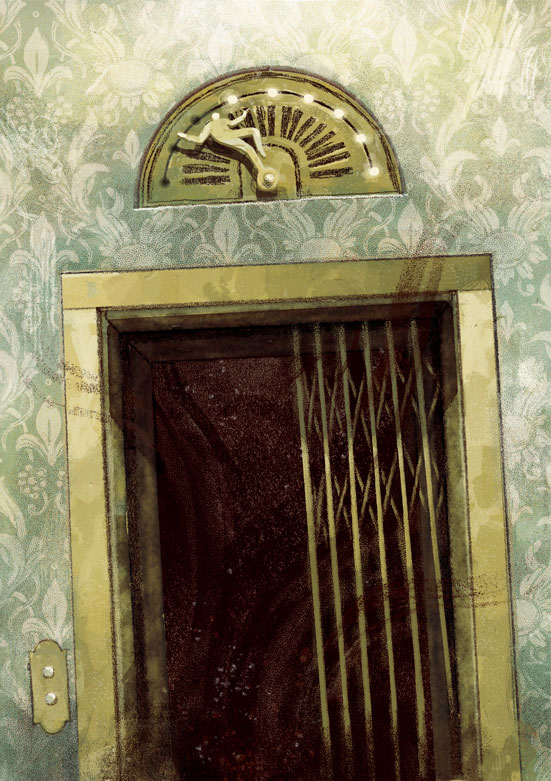

Cass inhaled deeply and stepped out of Nance’s sanctuary: His sanctuary he reminded himself, as he stood straight and walked down the hall to the private elevator. The public elevators had all been upgraded many times over the years. But this one stood with its door half-open. The original machinery had been replaced, but the car with its golden cage and faded 18th century silhouetted couples in wigs and finery still remained.

Cass intended this to be a central motif of his drama. It was here that the first death had blackened the Angouleme’s name and begun its legend.

The story was well known. Deep in the night of April 12, 1895, Nance—drunk, distracted, or both—thought he was stepping onto the elevator. Instead he went through the open door and fell nine stories to his death at the bottom of the elevator shaft. Rumor had it he was in pursuit of his daughter. Most accounts now considered it a murder.

The city inspector, a small, neatly dressed man, was in the elevator car examining the control panel. As Cass approached he caught the eye of Ms. Jackson, head of security for Sleep Walking. She gave an almost invisible nod and he understood that Inspector Jason Chen had accepted a green handshake.

By reputation Chen was honest and would stay bribed. But he was also smart enough to be quite wary of a major scandal wiping out his career. “Let’s talk,” he said, and Cass led the way back to the lair.

They sat in Nance’s old office with Cass’s lawyer linked to both. The inspector said, “Jackson tells me that twice a night you’re going to have that door open and the cage downstairs.”

Cass smiled and explained, “The car will only be a few feet below the floor so as to be out of the audience’s sight. Other than that it will just have regular usage.”

“I want Ms. Jackson and her people here every minute the door is open and the car is in that condition. And I want it locked every minute it’s not in use by your production while there are customers in the building. We will send observers.”

“I’m playing Nance,” Cass told him. “I’m the only one who’ll go through the door with the car not in place. And at my age I don’t take risks.”

The inspector shook his head. “It’s not you I’m worried about. I’m concerned about some spectators who have so little in their lives that they decide to become part of the show. We all know about them! My wife’s Spanish. She talks about espontáneos—the ones who used to jump into the ring during bullfights and get maimed or killed but became famous for a little while. People get desperate for attention. Like that one who torched himself at the Firebird ballet!

“Something like that happens with the elevator and they fire me, shut you down forever, and we’re up to our necks in indictments. Now let’s take a look at your insurance and permits.”

As he authorized documents with eye photos, Cass remembered an old show business joke: ‘A play is an original dramatic construction that has something wrong with the second act.’ His second act was the murder of the designer/performer Jacky Mac on these very premises. It happened seventy-five years after Nance’s death and was even more dramatic. What his play still needed was a third act.

Chen departed; the lawyer broke contact. Cass, half in costume, sat behind the huge, battered desk which Rosalin had found somewhere. His New York was the Big Arena, a tough city with a sharp divide between rich and poor, between a cruel, easily bored audience and the desperate artists. It seemed more like 1895 than not.

Cass felt he was looking for a main chance again, just as he had forty years and many roles before. He told himself that Edwin Lowery Nance, an entrepreneur in his fifties afloat with his daughter in the tumultuous late 19th century, must have had moments like this.

Like an echo of the thought, a child’s voice said, “Daddy! Thank you! I shall call her Mirabella!”

Startled, Cass/Nance looked up and found Evangeline Nance, with her long golden-honey hair and the 19th century Paris fashion doll she had named Mirabella tucked under her arm. Her eyes were shut and she didn’t appear to sleep walk so much as to float toward the door amid the smoke-blue silks of a flowing dress and sea of petticoats. Her satin slippers hardly seemed to touch the floor.

In character, Jacoby Cass picked up a pair of gold-rimmed pince-nez from the desk, put them on his nose and peered silently at his daughter

At the door Evangeline stopped, turned and nodded, satisfied she had his full attention. “We’re scheduled to do a run-through of the elevator chase. Remember, Mr. Nance?” she asked in a voice that was all New York actress. And suddenly Evangeline was Keri Mayne, a woman in her endlessly extended late thirties.

Keri had a history with Jacoby Cass—Ophelia to his Hamlet, a refuge fifteen years before when his third marriage broke down. The two had discussed Evangeline Nance. Her mother died when she was six. Over the twenty years before Evangeline became an orphan she remained a child and a sleep walker.

Kerri Mayne’s Evangeline threw open the door to the outer hallway and Jacoby Cass arose ready to be Edwin Lowery Nance. Researching his play Cass found no one solid account of the night of April 12, 1895. It seemed very likely that Evangeline sleep walked her way out of the apartment and the father followed. Servants had seen this happen before. No witnesses were available to testify about the April night.

In Cass’s script and performance, Nance rushed out of his office after her, calling, “Evangeline!” in a voice he felt would sound like cigar smoke and Scotch. “My child, where do you think you’re going?” he cried as Keri/Evangeline sailed down the hall. Cass wore more of Nance’s wardrobe: a vest, shoes that hurt his feet but somehow enhanced his performance.

Whispered rumor held that Evangeline had fled her bedroom with him in pursuit. And there was servants’ testimony that this had happened before.

Almost all tellings agreed that Nance, in the dim light thought Evangeline had gone to the elevator and stepped through the open door. He followed and found not Evangeline but a nine-story drop. How the elevator car happened not to be there was a matter of mystery and dispute.

With all that in mind, after an hour and a half of rehearsals, Cass/Nance called out “Evangeline!” for the tenth time. All this took place with late September light streaming through the windows. But Cass channeling Nance began to see it happening by moonlight and primitive bulbs. He had to dodge assistants and understudies who had been instructed to stand in his way, walk across his path just as the theatergoers would.

He actually lost sight of Keri/Evangeline before he reached the elevator. The faded gold door was wide open and she had to be inside the car. Nance hurried forward, stepped inside, and fell nine stories into the cellar. It was only three feet and the padding was well placed. But he screamed “EVANGELINE” and made it seem to fade as if coming out of Nance as he hurtled nine stories down.

Jackson and a burly assistant moved forward and would have blocked the line of sight had there been any audience.

Lying face down on the padding, Cass’s palm tingled and he read a message from Rosalin telling him that at 6:00 p.m. the Angouleme Hotel’s lobby would be ready and awaiting his approval. Rolling over, he looked up at Keri and Jackson staring down and made arrangements for a run-through of the lobby scene at 6:30.

Taking a director/playwright’s privilege, he wrote Evangeline into the scene. When the elevator door opened at 6:30 the lobby was all in shadows, low wattage light caught remnants of gold filigree on the walls. The three-story-high ceiling loomed above them with its mural of the European discovery of Manhattan still showing traces of grandeur.

The lobby was a collage of a hundred and seventy years of history. Singly and in groups, manikins lingered in corners and stairs. A sexual spectrum, enigmatic and sinister, they were dressed in 1970s miniskirts, flared pants, and psychedelic T-shirts, in 1890s bustles and floor-length gowns, in World War I doughboy uniforms. Some of their eyes seemed to reflect the light. One with dark hair, a red silk kerchief around his neck, and a leather jacket appeared to move slightly.

With his lovely daughter on his arm and the pair of wealthy customers alongside him, Cass/Nance surveyed them as if he saw the cream of New York society. When he said, “My good sir and lovely madam” and the rest of his opening lines, Cass had fully mastered his Nance voice, throaty and a bit choked with good living.

The actors playing the couple had their lines down. “But,” said the man, “what of the location here, almost on the docks and in a neighborhood of factories?”

“The anteroom of the Mighty Atlantic, sir! We shall steal the Hudson River’s thunder. This is meant to be a palace for my lovely princess, my daughter.” His daughter looked up at him, adoring but somehow lost.

The man frowned but the woman smiled and said, “How enchanting!”

“Come and partake of the Angouleme’s humble fare,” said Cass/Nance, and the quartet moved toward what had once been a famous hotel dining room and soon would be the Sleep Walking snack bar.

As they moved, Cass glanced at the front doors and saw them fly open right on cue. A long-haired figure in gold-rimmed dark glasses, an impeccably fitted velvet jacket and slacks strode across the empty lobby.

The young actor, Jeremy Knight, a rising star in the Big Arena, was Jacky Mac, dubbed the Kit Marlowe of late 1960s New York, whose murder was the Angouleme’s second famous death.

Before Jeremy Knight got any further, Cass stepped out of character and into the center of the space. He addressed the company, human and manikin alike: “Our city loves scandals. When current misconduct is too drab the city seeks out its past, desires old relics. This lobby reflects that perfectly.” Catching sight of her in the shadows, he bowed. “Thank you, Rosalin! But let’s remember that it’s only two weeks to opening night and there’s so much to be done.”

Everyone, cast and crew, applauded. He noticed that Keri Mayne, the charmer, and Jeremy Knight, the young lion, were talking together.

Rosalin led forward the production assistant who’d brought his coffee. “Sonya went out of her way to be helpful when I was acquiring props, saved us a lot of money. She has theatrical experience. There’s the silent part of the maid for which we were going to use one of Jackson’s people. She can do that and I could use her assistance.”

Cass looked at this tense young woman from deep in the artist underclass and wondered about Rosalin’s motives. But he was sure of her loyalty to this production into which she’d put so much invaluable work, if not to him. Sonya would come cheap and might be of use. So he nodded, smiled, and agreed with what was proposed.

When she and Sonya were alone Rosalin said, “I came to this city when it was first being called the Big Arena. Thirty years ago I was where you are now.” Rosalin had learned that Sonya had no family she could go to, no close friends outside the city. “I had nobody in this world and nothing but my work.”

TWO

Thursday night, at the 8pm show two weeks into the run, Keri Mayne leaned against the wall of Evangeline’s bedroom. In full costume, the flowing skirts made sitting both difficult and unwise.

She listened to Cass/Nance outside, saw his image on her palm—cameras were everywhere—heard him say, “Of course, J. P.,” into the wall telephone. Nance spoke loudly because he didn’t trust the instrument and because an audience needed to hear.

In the play it was well after midnight in the midst of the financial crisis of 1895 and J. P. Morgan had just called. “Of course I will stand with you, Mr. Morgan. Tomorrow at ten? I will be there, sir.”

Keri/Evangeline watched Sonya, in a European maid’s uniform, standing at the bedroom door and listening. In the intricately jealous context of a theater company Keri mistrusted and feared her.

Outside Nance said, “Of course, sir, I too know the loneliness of losing a wife.” His voice became muffled as he turned away. But those in the room could hear the great financier describe a need a discreet hotel keeper might satisfy. Nance had left behind him some nasty rumors and Cass had used all of them.

Keri/Evangeline heard the others in the room move closer to Nance, trying to catch the conversation. This was the moment. She nodded; Sonya threw open the door and Evangeline floated out of her room and into her father’s den.

Evangeline light as a package of feathers, was wrapped in silk. Shimmering hair flowed down to Evangeline’s waist,. Her eyes were half open, as if she was in a trance. She had Mirabella in her left arm. The gold slippers glided across the floor.

Half a dozen audience members were in the room. Women wore short skirts; men’s legs were concealed in trousers. These were the rich and Sleep Walking was a game as much as a play. Devices that enabled communication, blocked insects and rain, illuminated, cooled, or heated the area around one as the moment dictated were turned off. Mostly.

By clustering around Nance in the corner, the playgoers opened the way to the outer hall door which Sonya opened, revealing a crowd of eavesdroppers. She plowed through them. Seemingly unaware of all this Keri/Evangeline floated over the threshold. and maid and mistress passed down a dim lit hall.

Most of the windowpanes were blackened and heavily curtained. But an occasional one seemed to look onto the outside world. Playgoers on this floor could gaze out upon a 19th century night. Hologram pedestrians and horse-dawn vehicles traveled on the avenue, lanterns on ships bobbed on East River piers. Some figures in lighted windows across the way spoke intently at each other by lamplight while others seemed to grope naked in the dark.

“Evangeline!” she heard Nance cry as he came out the office door. Playgoers followed him. Figures in 19th century clothes discreetly got in their way. Audience members accidently blocked him. “My child, where are you going?” Nance cried to his daughter, who gave no sign she was aware of him.

Playgoers were supposed to be absolutely silent. But a man whispered, “She’s a bit taller than I would have thought.” And a woman responded, “Looks like a child and at the same time older.” Sonya kept them away.

Though their conversation irritated Keri, she did prize her ability to alternate between radiant child and disturbed adult. All was shadows and misdirection at the end of the hall. Evangeline floated toward the open elevator door.

Nance, in a voice that was authoritarian and pleading at the same time, shouted, “Young lady, you must obey me. Stop!” His heavy shoes banged on the floor as he began to run.

For a moment everyone looked his way. When they looked back to the elevator, Evangeline and her maid had disappeared.

Edwin Lowery Nance, who managed to appear to hurry while not really moving quickly, came down the hall. He ran through the open doorway and his shout turned into a scream. His voice faded as he fell nine stories into the cellar.

Jackson and her equally big cohort, dressed in 1890’s street clothes, were suddenly there blocking the audience members’ view. She and her partner looked into the pit. The partner screamed. “Someone get a doctor! Call the police!” Ms. Jackson shook her head sadly and pulled the elevator door closed.

“I saw him, his body was all bloody and smashed,” a theatergoer cried.

Keri—standing inside the door that led to the servants’ stairs—listened, amused by this. Someone was always getting caught up in the drama. She imagined Cass/Nance lying on the padding, looking up at the faded fleur-de-lis design on the elevator car’s roof and, like her, taking the cry as a kind of applause. When reviews called the show “Just a Halloween entertainment,” Cass told her, “That gets us through the next month. After that we’ll find something else.” She hoped he was right.

Her costume made stairs difficult and the maid reached out to help her. Sonya spoke, voice low and intense: “Just after Nance fell they thought it was a tragic accident. Then rumors started that I was seen near the elevator machinery in the cellar. I disappeared before I could be questioned about the events and was never seen again.”

At moments when Sonya identified with the part of Evangeline’s maid like this Keri wondered why Rosalin, who took care of so many things, had arranged for this person to be alone with her in two performances a night, six nights a week. She hoped Sonya was aware how vital to the production her Evangeline was. Surveillance cams were everywhere but she wondered if they didn’t just offer a greater chance for immortality.

So she gazed at Sonya with admiration and delight (and none could look with as much admiration and delight as she). “I’m amazed at the amount of research you’ve done. You have the makings of an actor,” she said.

Then, as Evangeline, she motioned Sonya to go first, and said in a breathless child voice, “After Nance’s death rumors got in the papers. One of my dolls was supposedly found in the elevator with his corpse. It’s when the term ‘Angouleme Murder’ began being used. Servants testified that Nance had always taken an unnatural interest in his daughter.” Here Evangeline covered her eyes for a moment. But Keri managed to catch Sonya’s expression of both horror and sympathy.

Their destination was the sixth floor. On the landing, they paused, heard a 1920s Gershwin tune played by a jazz pianist. Privately, Keri was certain Evangeline had killed her old man, who in every way deserved it. Life with him and after him had made her a manipulative crazy person. It was what Keri loved about the part.

But she looked at Sonya and said with great sincerity, “I try to remember what that poor child-woman went through and put that into my performance.”

Sonya held a light and a mirror like this was a sacred ritual. Evangeline’s haunted face—just a trifle worn—appeared. Keri Mayne did a couple of makeup adjustments, held the doll to her chest, and braced herself.

Sonya opened the door and followed as Evangeline half floated into a hallway with distant, slightly flickering lights. Keri paused, listened for a moment, then wafted toward the music.

Playgoers, drinks in hand, stared out a window into a hologram of a lamp lit street scene. A big square-built convertible rolled by with its top down and men and women in fur coats waving glasses over their heads, while a cop made a point of not looking. Flappers in cloche hats and tight skirts scurried to avoid getting run down. They gained the sidewalk and disappeared into the Angouleme’s main door downstairs.

On the sixth floor it was 1929.

It took a few moments for the well-upholstered crowd to notice the sleep walker and the woman in a maid’s uniform who guided her.

Keri heard their whispered conversations:

“ . . . maybe down here trying to avoid her father?”

“ . . . a little older, this is long afterwards, when he’s dead and she’s still living here.”

“We missed his big moment.”

“ . . . looks like she’s been on opium for years.”

“Morphine, actually.”

“Creepy, just like the Angouleme!”

“But delicious!”

“ . . . like a ghost in her own hotel for decades after the murder.”

The illicit, low-level whispering was the audience telling each other the story they’d seen and heard online. Cass had wanted that. “Makes it like opera or Shakespeare, where the audience knows the plot but not how it’ll be twisted this time.”

On the sixth floor Keri was Evangeline in the long years after her father’s death and before she died in 1932 addicted, isolated. Even before the First World War the Angouleme was called “louche” when that was the word used by people too nice to mention any specific decadence.

“She looks like she’s hurt!” murmured a playgoer in a lavish, shimmering suit as he moved toward Evangeline. Keri lurched the other way, Sonya got between them.

Always in these audiences were ones like this who wanted to be part of the drama. If there was a long run, their faces would appear again and again. Certain people would start going out in public dressed like characters in the play. Great publicity, but a warning that no one should get too immersed in a part.

“Oh, who are all these ghosts, Marie?” Evangeline asked her maid in a whispery child voice and looked around at the faces staring at her. “People like these weren’t allowed in the Angouleme when Father was here.” She held up the doll. “Mirabella was his last gift to me.”

She could hear the crowd murmur at this, felt them closing in. And in that moment, the character Jacoby Cass’s script simply called “The Killer” came down the hall. This young man wore a leather jacket and a red silk kerchief tied around his neck. The butt of a revolver was visible in a pocket. The actor looked at Evangeline and the rest of the crowd with a cold, dead-eyed stare.

“How did he get in here?” a man whispered. “Where’s security?”

This amused his partner. “More than likely he’s a fugitive from the Jacky Mac Studio downstairs,” she said. “We must pay a visit.”

For a moment all attention focused on The Killer. Evangeline wobbling slightly, continued to the jazz piano.

By the 1920s, a louche, scandalous hotel had become attractive to certain people. Artists stayed at the Angouleme and entertained there: French Surrealists and their mistresses, wealthy bohemians poets from Greenwich Village, Broadway composers looking for someplace out of the way but not too far.

Something between a party and a cabaret went on in the living room of Gershwin’s suite. Around the door, slender, elegant flappers leaned towards smiling men in evening clothes. The lights were soft; it usually took a couple of glances before someone would recognize them as manikins. But then the silvery figure, you were sure was a statue, would turn slightly and a pair of dark eyes would hold yours for a moment.

Inside the room a musician who looked not unlike Gershwin sat at a baby grand and played the sketches that would become An American in Paris.

The suite was set up as a speakeasy where audience members bought drinks, leaned on furniture, listened but also watched. Evangeline shimmered before them, exchanged a long kiss with the silver flapper. All eyes were on the two and Gershwin played a slow fox-trot. As they danced he turned from the piano, looked to the audience as though asking if they saw what he did.

When theatergoers from the hall began to crowd into the room, Evangeline floated through a bedroom door and her maid closed it. When people opened it to follow her, they found the room was empty and the door on the opposite wall was locked.

Some at that point would realize that the sixth floor was a diversion, a place to spend money and waste time that would have been better spent up in the penthouse or downstairs where a murder was brewing.

Sonya brought Keri/Evangeline down to the third floor where her next scene would be. The maid character didn’t appear again in Sleep Walking. “I feel like I should stay with you,” she said, and opened the door.

Keri grasped her arm, looked into her eyes and said, “You’ve done enough. You’re wonderful.”

The next day Sonya was setting up antique wooden folding chairs in Studio Mac on the third floor. She said, “I wish my part was bigger. I want to be in every minute of this play. I know that’s how actors feel.”

Rosalin believed the intensity could possibly be of use. “The Big Arena is a savage place, run for the very rich and full of the superfluous young. Most of them will never find something larger than themselves as you are doing. It takes a certain kind of personal sacrifice to fully achieve this. But it will live in others’ memories.”

THREE

In New York it was shortly before midnight of Halloween 2060. Over the years, this holiday had surpassed New Year’s Eve as the city’s expression of its identity. Especially at times like this when the legendary metropolis was short of cash and looking for some new idea to carry it forward.

In the Angouleme it was time for a special midnight show. Playgoers entered Sleep Walking through the lobby. From there they either went up the stairs, waited for the elevators, or just looked for a place to sit while getting acclimated. Rosalin had managed to exploit the lobby’s disreputable, fallen majesty. It was a place made for loitering. Upstairs each floor was set in a different decade. The lobby celebrated the entire sordid past. Here, a cluster of 1960s rent boys lingered in the shadows next to the main staircase and several 1900s ladies of the evening in big hats and bustles stood near the ever-vacant concierge desk.

Jeremy Knight waited in a side doorway of the building. At exactly five minutes after the final stroke of twelve he got the one-minute signal, walked a few feet down the sidewalk to the front of the hotel, and was flanked by security.

They threw open the doors and Knight/Jacky entered the lobby: tall and wire-thin, his eyes hidden behind dark glasses, his blond hair in a ponytail down almost to his ass.

Knight was irritated as he always was at this moment by the sight of Jacoby Cass, who, with his speech about the God-given 19th century being finished, was making a grand exit with his party. A few patrons tried to follow but found themselves blocked by Jackson and company.

Jeremy Knight marveled at the number of scene-stealing opportunities Cass, that shameless ham had managed to insert into the script.

Knight surveyed the crowd. The show was booked solid for the Halloween weekend. Advance sales were another matter and his guts turned cold whenever that crossed his mind. So he didn’t think about it.

In fact, Cass’s distraction allowed Knight to be through the crowd before they were aware of him. He turned then to face them and they saw Jacky Mac—couturier, poet, playwright, in a classic outfit of his own design: V-shaped, slim-waisted jacket; bell-bottom trousers; a wide tie with bright pop art flowers that looked like faces. Jacky Mac had been known to wear miniskirts and silver knee boots, but not on this occasion.

On cue, the public elevator’s doors opened. Customers hesitated as always about getting on board because of the legends surrounding the place.

Of Jeremy Knight it had been written, “He was born to wear a costume; put him in anything from a 1940 RAF uniform to a pink tutu and he is transformed.” He despised the description but had found that in roles like this an actor grabbed inspiration wherever it could be found.

Without missing a beat, Jacky Mac stepped backwards onto an elevator and seemed amused by the audience’s fear. “Oh, it’s safe!” He somehow murmured and shouted in the same breath. “And if it begins to fall, just do as I do: flap your arms and fly!”

From the elevator doorway, Mac gazed at the manikins in the corner, saw something, and nodded. The audience watched fascinated as one of the figures, dressed in leather and a blood red kerchief stepped out of the shadows and walked unsmiling into the car. “I was crucified just now by his glance,” Jacky announced as The Killer joined him and the door closed.

Alone, without an audience to overhear them, Jeremy and Remo, the young actor who played The Killer, didn’t exchange a word. Each got off on a different floor, and over the next hour made rehearsed appearances in dark halls and bright interiors.

Forty minutes into the play, Jeremy Knight/Jacky Mac listened to Gershwin’s piano and heard Nance’s death scream. Ten minutes after that he did a huge double take when he passed the ghost of Evangeline on the tiresome seventh floor where it was always 2010 and the well-lighted halls were lined with display windows offering overpriced Sleep Walking souvenirs. Coming down the servants’ stairs five minutes later, he passed Sonya trudging up carrying costumes. He smiled and she looked at him as wide-eyed as any fan.

Halloween week was great. Capacity crowds were willing and able to laugh and scream at every performance. On the third floor of the Angouleme two weeks later, at about an hour and twenty minutes into Sleep Walking, Knight/Jacky climbed onto the small stage in the Mac Studio and felt the difference.

The Studio included a large performance space with sixty chairs set up. At the Halloween midnight show all seats had been taken and many more patrons stood or sat on the floor. Halloween had been a triumph. But it’s in the weeks between holidays that hit shows are revealed and flops begin to die.

Jeremy Knight had that in mind as he pirouetted on the stage. He estimated thirty people in the seats. And this included The Killer, always the first to arrive. Remo was also Jeremy Knight’s understudy. He sat down front with his legs stuck out so far his booted feet rested on the stage. A little knowledge of history and one would be reminded of Jacky Mac’s fatal tastes.

The under-capacity crowd bothered Knight. But he told himself that any audience of any size was fated to be his. And the people at these performances who sat on antique wooden folding chairs were willing extras.

They were drawn to the Studio by the sounds and the lights flashing through the open double doors. Or they were told not to miss this by friends who had seen Knight/Jacky perform this monologue, one-man play, stand-up routine, whatever you wanted to call it. Jacky Mac’s writing was out of copyright and Cass had lifted big chunks of it for a play within a play called A Death Made for Speculation.

Jacky leaned over the front of the stage, hummed a few bars of music, and said in a husky voice, “I’d thought of coming out in an evening gown and doing a Dietrich medley. But I’ve seen the way women look at me when I do drag. It’s the look Negroes get when a white person sings the blues. So I’m here to fulfill a secret dream. I’m playing a guy.”

Rosalin had taken liberties with the decor but 1970 was a hard moment to exaggerate. Jacky’s loft had been described and shown in articles, books, and documentary footage. Like Warhol’s factory, it was iconic. On the walls and above mantelpieces were mirrors, which at certain angles turned into windows looking into other rooms. In those rooms doll automata played cards, a mechanical rogue and his partner cavorted, and one or both might look your way, indicate you were next.

“When I was young,” Jacky Mac said, “I tried to make myself look beautiful. Later I tried to make myself look young. Now I’m satisfied with making myself look different.”

In the lawless 1960s, the Angouleme Hotel was almost as famous as the Chelsea across town. When it was sold as co-op apartments and lofts Jacky bought most of the third floor of the building with the proceeds of his clothing line and his performance art. Jacky Mac was not, of course, his real name, which was boring and provincial Donald Sprang.

For Jeremy Knight the task was making something as ordinary as homosexuality feel as mysterious, hysterical, and dangerous as Jacky had found his life to be. A brief film clip existed of Jacky Mac working out some of this material in the Studio, performing for an audience of friends in just this manner.

Jeremy caught the odd, fluid near-dance of Jacky Mac, which he’d learned from old videos. On the walls Hendrix, Joplin, and Day-Glo acrylic nude boys and girls melted into a landscape of red and blue trees. A light show played intermittently on the ceiling. Deep yellow blobs turned into crisp light green snakes, which drowned in orange, quivering jelly. The color spectrum dazed the eye.

Knight/Jacky leaned forward to show a once-angelic face now touched with lines and makeup and asked, “Why do men over thirty with long hair always look like their mothers?”

On cue, The Killer down front swallowed a few pills, stood up, pulled a bottle from his back pocket, spat out, “Faggot” at Jacky and walked toward the door while taking a long slug. In the old-fashioned manner, Jacky Mac liked his partners rough. It would be the death of him.

The audience watched the long, slow exit. Wrist limp, Jacky Mac gestured after him. “We have the perfect relationship. I pretend he doesn’t exist and he pretends that he does.”

It wasn’t just the costume; Jeremy Knight had absorbed every bit of the lost manner and voice of someone society hated for what he was. Ninety years later it was hard to convey. For a few years in his teens Jeremy had been Jenna Knight, making the change because boys in school got neglected and there was an advantage to being a boy with the mind of a girl.

Each day Knight felt closer to Jacky’s alienation. Saw it intertwine with his own fear of falling off a very small pedestal and back into the vast, penniless crowd in the Big Arena.

The Killer stopped at the door and yelled, “IT’S YOUR TURN NOW, BITCH” at somebody no one could see.

Jacky glanced his way, turned back to the seats and found everyone staring wide-eyed. “Dear me, are the snakes growing out of my head again? That Medusa look was so popular once upon a time!” He peered at the crowd and remarked half to himself, “Judging by your faces, I’ve turned you all to stone. Forgive me. My mother always said . . .”

But few were listening. All eyes were on a figure in silks floating past the stage humming “Beautiful Dreamer” under her breath, while the audience whispered her name.

Cass had invented a liaison in this hotel between a self-destructive artist and the ghost of a legendary suspected murderess. The character Jacky was haunted by Evangeline decades after she had died of an overdose.

Once he caught sight of her he seemed to forget the audience completely and followed her out of the room. When audience members came after them, they found a locked door.

But the room into which the two had gone was Jacky’s legendary mirrored bedroom. The ceiling, an entire wall, even the floor in places reflected the room and its outsize bed. One wall was a two-way mirror. Jacky was always aware of this, as were some of his bedmates.

The Sleep Walking audience flocked around the glass, saw silhouettes dance in semi-darkness as Jacky tried to trap Evangeline or she ensnared him. One shadow seemed to pass through another. One or the other always had a back to the audience and both whispered so none outside could hear.

“How’s the gate tonight?” she asked.

“Seventy percent for this show, about the same for the midnight show,” he said.

“Shit,” she said. “It’s going to fold.”

“Needs a third act,” he said. “I have my eye out for especially unstable repeat patrons.”

“A third victim,” she said. “Rosalin’s got one but Sonya scares me.”

He shook his head. “She’s harmless.”

“A suicide might do,” Keri said.

“I volunteer my understudy, Remo.”

“Silly, understudies don’t want to die; they want to kill the leads.”

Through the glass the two heard, “Where are you, faggot? Fucking the ghost girl?” The Killer had returned.

Jeremy Knight took a deep breath and walked out of the bedroom. “Let’s talk, one faggot to another. I’m the terrible secret: the herpes sore on the ten-inch cock, the skunk at the tea dance, the troll without the decency to hide under the bridge. I’m the one who’s here to call you sister, to tell you . . .”

In Sleep Walking The Killer emptied the pistol into him just as had happened in real life. Audience members screamed. Keri always stayed for this and always had to stop herself from crying. Then she’d slip out for her big scene with Nance.

Only after his death was Jacky Mac described as “The Kit Marlowe of this bedraggled city.” The press didn’t get into the details of his life. The murderer was never identified, never caught.

Business did pick up for Christmas/New Year. But January brought bad weather and bad box office. On the last performance that month Rosalin stood several steps above Sonya, looking down at her as she said “This show needed something that would get the Big Arena talking about us and not the thousand other entertainments available. That never happened. We’re posting closing notices next week. All my work wasted. I hope you enjoyed your brief time on stage.”

Sonya’s eyes glistened. Rosalin recognized tears. They had talked about suicide. But heights bothered the stupid girl, guns were a mystery. Rosalin had thought to bring a knife.

FINALE

The show’s final scene was actors playing detectives, questioning the audience members as they filed out of the Studio after Jacky Mac’s death.

And down the hall, Edwin Lowery and Evangeline Nance went at each other in hoarse ghost whispers. “Oh finally, my daughter, you will have no more to do with that sodomite!” Anger is never hard for actors to achieve in a failing production.

Keri was scared and irritated. Sonya, like a rat deserting a sinking ship, hadn’t shown up that evening to get her through the dwindling crowd. She screeched, “So unlike the midnight visits to my room when I was still a child! Let us talk about pederasty and hypocrisy!”

Playgoers, still a bit ensnared by the drama they’d just witnessed, kept pointing them out to the actors/police who would look but be unable to see the ghosts.

“And that reminds me, dear Father . . .” Evangeline started to say, when there was a long, piercing and—Keri realized—quite heartfelt scream.

“That sounds very authentic!” said Jacoby Cass in his own voice and with a look of hope in his eyes.

Actor/cops and audience members stared down the hall. The Killer was running toward them with tears in his eyes and the prop gun still in his hand, babbling. “. . . in the elevator . . . opened the door . . . blood . . .”

Jeremy Knight/Jacky Mac arose from the floor of the Studio to discover what the commotion outside was about and was stunned when Remo/The Killer threw himself sobbing into his arms.

City police found Sonya holding open the faded gold door of the elevator. She’d knocked Rosalin down and stabbed her multiple times. The surveillance tape showed it all. She’d even looked up and waved.

When they hustled her out of the hotel and into a police car, Sonya yelled to the crowd, “She wanted me to die, wanted somebody else to die. But her work was over and the play must go on!”

A reporter asked Cass, “City officials think the production can open again in another few days. Do you believe it’s safe for theatergoers?”

Jacoby Cass had heard from Inspector Chen that the authorities regarded this as a murder that could have taken place anywhere. The elevator, though, would need to be thoroughly inspected and his supervisors would accompany him.

Cass anticipated a flurry of green handshakes but knew Sleep Walking Now and Then was booked solid for at least the next six months. He told the reporter, “Yes. Notice that at no time was the life of any patron threatened!”

“Is the place haunted,” Keri Mayne was constantly asked.

Leaving the building the night of the murder, she had felt Rosalin’s presence in the lobby and wondered if her death was her greatest piece of theatrical design. Until then Keri hadn’t thought much about spirits. “Yes,” she always said. “And I’m dedicating each of my future performances to the ghosts.”

Seeing Jeremy Knight and Remo arrive at a party as a couple, a social blogger asked, “Does this feel like your on-stage relationship?”

Remo shook his head. Jeremy stopped smiling for a moment and said, “Yes.”

As a foreign correspondent put it, “The Big Arena was made for moments like this.”

“Sleep Walking Now and Then” copyright © 2014 by Richard Bowes

Art copyright © 2014 by Richie Pope